In my last post, I discussed some of my ideas for flipping the classroom in the Social Sciences/Humanities. In this post I turn to a different theme – literacy – which has surfaced as an important and recurring topic in the Technology Fellows Program (TFP) meetings. In fact, the topic has come up so often, that this past summer, I participated on a conference panel about digital technologies, metaliteracy, and faculty-library collaborations at the Connecticut Information Literacy Conference (CILC). Joining me on the panel were my colleagues in Information Services, Laura Little, Instructional Designer/Developer, and Jessica McCullough, Instructional Design Librarian.

One major theme of our panel was that the TFP has become a welcome yet unanticipated venue where faculty, instructional technologists and librarians are collaborating on student literacies. We, the Technology Fellows, have found ourselves devoting a significant amount of time to discussing the links between teaching, digital technologies, and literacy-building. We have also found ourselves relying extensively on the expert knowledge that our colleagues in Information Services bring to the table as we think about revising some of our courses for spring 2015.

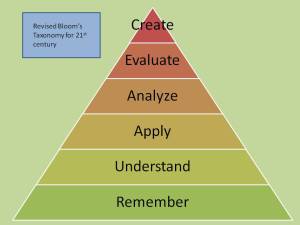

This topic emerged unexpectedly during a conversation about the ways in which digital technologies can support the delivery of course content. Examples spanned the gamut from showing YouTube videos in class, creating and embedding video in Moodle web pages, and developing original media for interactive digital textbooks. While the possibilities were intriguing, our conversation soon segued into a different discussion on how multimedia – e.g. online video, interactive web sites, or user-created Wiki pages – can facilitate so-called “higher cognitive levels of learning” as suggested by Bloom’s taxonomy of pedagogical objectives.

Digital technologies can certainly help students to better “remember” and “understand” course content. Moreover, they can also teach them to “analyze,” “evaluate,” and eventually “create” knowledge in relevant ways. Online videos are not only useful for sharing information, but they can also foster student thinking about the purposes, target audience, goals, biases, and historical contexts of both analog and digital sources. Likewise, in using prominent user-created sites (e.g. Wikipedia), rich discussions can ensue on the benefits and dangers of open-source sharing and democratic knowledge production. As Historian and American Studies expert Jeffrey McClurken has commented, digital technologies can “create opportunities for students to become ‘critical practitioners’ of digital media rather than passive consumers or users.” An important rationale for using digital media, he argues, is the “notion of students creating and writing for a public audience … which has clear benefits for the students, the teacher and the institution” and “open[s] up the traditional, closed system of knowledge production” (Teaching and Learning with Omeka: Discomfort, Play, and Creating Public, Online, Digital Collections).

Upon further deliberation, the Technology Fellows have come to the consensus that the value in using digital technologies extends well beyond simply exposing students to new information or technological tools. Indeed, current scholarship shows that digitized curricula can offer new opportunities for developing a sophisticated range of information literacies, including information technological fluency, and digital, visual, and media literacies. Library and information scientists, Thomas P. Mackey and Trudi E. Jacobson (the keynote speakers at CILC) developed the term “metaliteracy” to draw attention to “multiple literacy types.” As knowledge becomes “increasingly participatory” and “takes many forms online,” they suggest, the consumption, sharing, and production of knowledge requires an increasingly “comprehensive” approach and reflexive “understanding of information.” (Reframing Information Literacy as a Metaliteracy).

Personally, I have found this notion of metaliteracy especially compelling as the College moves forward to revise General Education requirements and debates the types of “knowledge” or “competencies” that are relevant to the liberal arts curriculum in the 21st century. The framework of metaliteracy allows us to articulate and embrace the multiple modes of knowledge production that students will certainly have to navigate in order to participate in increasingly digitized and networked information environments. At a minimum, teaching students to consume and produce knowledge accurately, creatively, collaboratively, and responsibly will require a new awareness of the ways in which new networked modalities – online media, platforms, and tools – are changing knowledge formation in our respective disciplines.